The Power of Life Stories in Health Care

Every person has a story to tell. Storytelling is something we have experienced around the kitchen table or a warm campfire. Tales of great joy, tragedy, adventure, or love are told as we share our own human experiences with each other. Narrative and reminiscing are appropriate and useful in health care (narrative medicine, narrative care, humanities in medicine). It is also useful in daily life because: 1) Nearly anyone can participate in life review; 2) Life stories can help with a positive sense of identity; and 3) As people reach the end of their lives, it can result in integrity and reconciliation (Kenyon, et al. 2011, p. 291-292). It is especially helpful in the lives of older people as psychiatrist Dr. Robert Butler first documented in 1963; it comes naturally to reminisce with the familiarity and comfort of sharing about one’s past experiences, especially as people reach into their 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s, and beyond.

People may say, “My life is a mess,” “My life is a battle,” or “My life is a journey,” and all these things may be true and appropriate metaphors. However, the metaphor “life-as-story” is an appropriate framework for daily life (Randall, 2015). It provides a tool to use in therapeutic situations to help people see how they have viewed life in the past and how it could, essentially, change by “re-storying” it (or restore it) for a better future.

Each of our lives is part of a larger story of community and culture. We are entwined with other’s stories with successes, conflicts, tensions, and failures that connect one story into the next. Gerontology and geriatric medicine are tied to all of this. We cannot ignore the impact of aging and the life course on an individual’s mental health. “As we age and change and assume greater agency overall, we—theoretically—have more say in our narrative development, more ‘authority’ in the story of my life. Thus, all of us are artists at heart, and novelists at base….We fashion it, not in a book, however, but in memory and imagination,” (Randall, 2015, p. 55). There is great truth in Alex Haley’s quote, “Every time an old person dies, it’s like a library burns down.”

Older adults sometimes face difficult chapters of their lives that may require “restorying” to find meaning or resolution. In the lives of older adults, the idea of life-as-story can help people change chapters from “I’m a failure” to “I’m a survivor” (or even “That was embarrassing!” to “That was funny!”), which is useful and freeing. Sometimes people need to be encouraged. “You made it through” or “You are stronger now, after living through this difficult chapter of your life.” Narrative can go hand in hand with resilience and help people experience more optimism and self-worth. “There is no one else like me,” a person may feel after they begin to open their minds to memories and his or her unique human journey.

Telling one’s story can require courage as in the case of veterans with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Narrative care involves them composing or sharing out loud their stories again and again to reduce some of the power the story has had over their lives. Not every veteran is ready, willing, or able to participate in this. However, some veterans, especially as they reach their 70s and beyond, may decide to do this if given an opportunity for someone to listen in a safe environment, with counseling available if needed. This is an approach to consider for others who have experienced trauma.

Looking back on stories and memories, can be a time of self-discovery. We recall the people, places, and life events that have had an impact. Sometimes memories are a reminder of something we loved to do as children. As the biography unfolds, it can reignite passion for this activity or interest again, which contributes to positive aging and wellbeing. Also, telling stories can lead to a lasting legacy and teaching and informing younger generations about parents, grandparents, or life events. A legacy brings a sense of peace and hope for the future.

The family tree can come to life (truly getting to know past and even present generations through stories), which gives older people a stronger sense of purpose and meaning when it can be shared. Purpose and meaning makes life worth living—and health worth maintaining. In one’s own story, it is also helpful to see the pattern of this event led to that event…which led to the next event. The “plan” of life, which may have seemed disordered at the time, may come into focus as an autobiography unfolds or just even one story is told, weaving together multiple people’s stories in some cases. This can contribute to emotional and spiritual wellbeing, areas which do not typically receive enough attention in health care.

Narrative, spirituality, and aging are three areas that merge in research and in life. Everyday conversations among older people can go deeper as they share the details of a particular day. It can be stories within stories as they know their family, their community, and its history. Stories are a good way to recall and connect with one another, and social connection is critical when loneliness has such major health risks.

Reminiscence can be used with people who face memory challenges as well. I was able to converse with a man for at least 30 minutes about his wedding day, when we first met at a Texas memory care community. We were instantly connected. The details did not matter as he could not recall those (and they were not important in this case). He did not know when or where the wedding was, but he could describe his blue tuxedo, the heat of the day, the beauty of his bride, and how lovely the church looked. The story pulled me in, and he “lit up” as he shared with me. The bond that comes from even a “quick” story shared cannot be denied, whether it is at a hospital bed, in a nursing home, or in a retirement community. Imagine a day when the electronic health record can provide even a short bio of the person as a whole person. Stories are excellent for building intergenerational relationships too, both young and old gain immensely from these experiences. Even a “quick read” of the data in a LifeBio Snapshot (a life story summary) could give clinicians and other health professionals a genuine bond with the person receiving care.

Narrative has the power to build compassion, and this is a key part of “narrative care” in health care environments. “To be compassionate toward others is to entertain a story of them into which we could easily insert ourselves. It’s to appreciate that their life story is as mysterious and unfathomable as our own. It’s to see our story in their story, and their story in ours,” (Randall, 2015, p. 123). When we know the whole person, or at least more about their emotional and spiritual life, it results in a holistic view and not just a focus on physical problems the person is having. Sometimes someone is just experiencing intense loneliness, helplessness, or boredom. Connecting is key to help people experiencing hospital delirium too. Narrative and storytelling are appropriate interventions to bring comfort and to increase socialization.

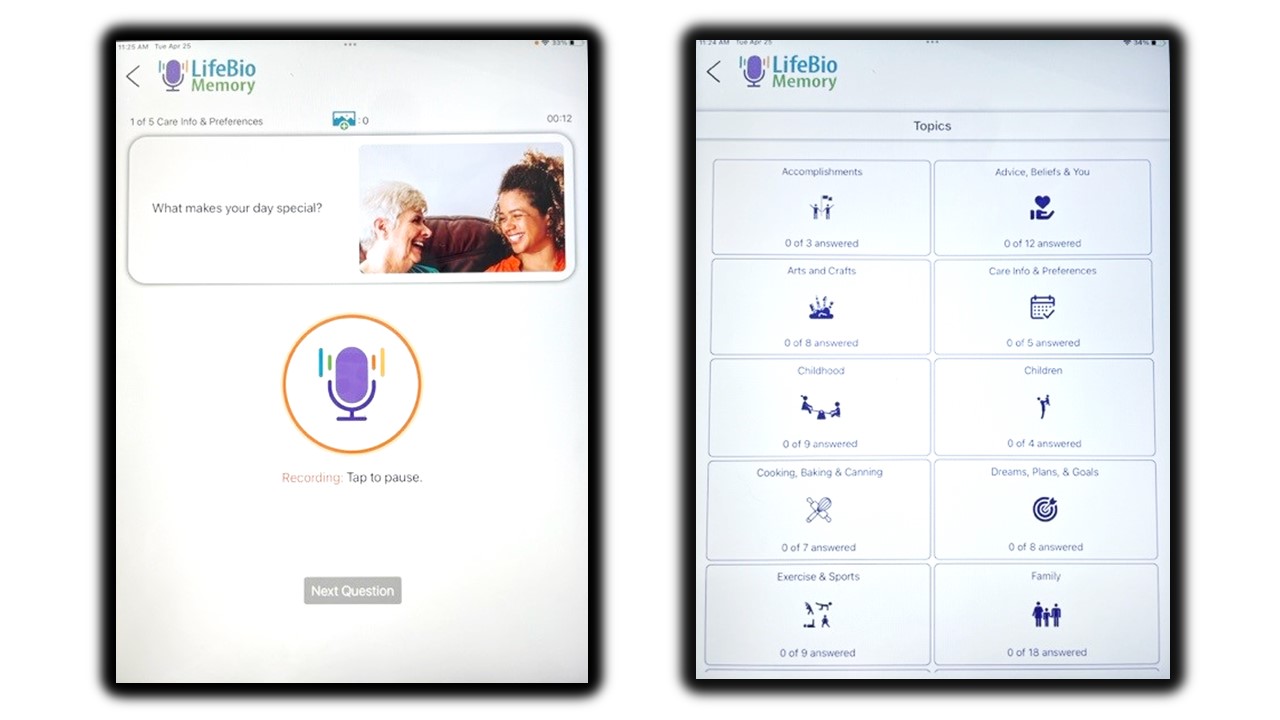

People need to be given permission to tell their stories. They may think they have nothing to say, or “nobody wants to hear my story.” Tools like LifeBio’s Memory Journal or online biography at www.lifebio.com are giving people the template of appropriate, specific questions needed to know where to start and what topics matter. Childhood memories, work experiences, love and marriage, and family relationships are just a few of the many topics that a person explores. In the case of health care settings, the key is empowering people with tools and then activating resources for social engagement, ideally, whether that is family, volunteers, or staff members. When the space and time to connect is given as a standard routine, the patient experience and satisfaction with service and care will improve. It is a good goal to build relationships with more depth beyond physical care conversations.

Narrative is an excellent social connector. Therefore, it can also help with one of the most expensive challenges facing health care today: loneliness and social isolation as a health risk. It can reach people where they are at home, even with a phone call (MyHello) with the goal of reminiscing for a short time together each week. The relationship matters. We will continue to encourage people to be good storytellers, story listeners, and advocates for the many people who have narratives just waiting to be told. Our conversations do not need to revolve around the weather or just physical problems. It is time to learn and gain wisdom from the journey of aging and the remarkable biographies that unfold. Every person has a story to tell.

References:

Butler, R. (1963) The Life Review: An Interpretation of Reminiscence in the Aged, Psychiatry, 26:1, 65-76, DOI: 10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

Kenyon, G., Bohlmeijer, E., Randall, W. (2011). Storying Later Life: Issues, Investigations, and Interventions in Narrative Gerontology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Randall. W. (2015). The Narrative Complexity of Ordinary Life: Tales from the Coffee Shop. New York, Oxford University Press.

Sanders, L. (2010). Memory Journal. Marysville, LifeBio, Inc. www.lifebio.com

- Life stories in health care,

- reminiscence and health care,

- Psychiatrist Dr. Robert Butler,

- Life as story,

- storytelling as self-discovery,

- narrative spirituality and aging,

- reminiscence,

- reminscence with memory challenges,

- overcome loneliness,

- LifeBio Memory Journal,

- Narrative as social connector,

- MyHello,

- Storying Later LIfe G. Kenyon,

- The Narrative Complexity of Ordinary Life by W. Randall