Experiences of Loneliness, Social Isolation, & Solitude for Older Adults

In the U.S. and worldwide, there is mounting evidence that loneliness and social isolation are growing problems that lead to major health risks and personal distress. There is also growing understanding of the value of solitude and its impact on positive states of wellbeing for older adults. Related to these topics, issues that come from experiences of dementia, widowhood and grief, problems that occur in residential care or nursing homes, spirituality and faith, and lessons from centenarians will be specifically examined in their relation to loneliness, isolation, and solitude.

As a starting point, what are ways to define loneliness, isolation, and solitude? Loneliness is a discrepancy between an individual’s desired social contacts and his or her actual social contacts. It is a negative feeling of not having enough affection or closeness to a significant person or to close family or friends. People can experience loneliness in a room full of people or even feel detached from a spouse or partner in the same room. A lonely person may be unable to have the quantity or quality of social connections they prefer. Unlike the subjectiveness of loneliness, social isolation is the objective fact that a person may have minimal social contacts for a variety of reasons. This article will also describe a related idea which is solitude. Solitude is an opportunity to be alone voluntarily to recharge or to be creative, unlike loneliness that is involuntary and even feared or dreaded (Ong et al., 2016).

A growing body of research shows that loneliness is a major problem in the United States and worldwide. Loneliness and lack of social connections affect both mental and physical health. In 2010, Holt-Lunstad, Smith, and Layton, examined the quality and quantity of individuals’ social relationships and how these relationships impacted mortality. Data was extracted from 148 studies from 308,849 participants primarily from North American (51%), Europe (37%), Asia (11%), and Australia (1%). The study looked at participant characteristics (cause of death, initial health status, pre-existing conditions). The research was groundbreaking for its size, and it indicated a 50 percent increased likelihood of survival for participants with stronger social relationships. Poor quality of social relationships, of which loneliness is one result, was linked to early mortality at a rate comparable to other risk factors for death such as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, obesity, or physical inactivity. This study has been pivotal in raising awareness of the problem of loneliness.

Leadership in addressing loneliness as a significant problem has come from the United Kingdom. In 2011, they established the Campaign to End Loneliness and outreach to older adults began across the U.K. with charity and government support. Over time, more interest in this area grew out of lawmaker Jo Cox’s efforts to address loneliness. Unfortunately, Cox’s life was cut short by a radical in 2016. As a response to Cox’s death and with a growing problem at hand, in January 2018, the U.K. Prime Minister became the first country to designate a minister of loneliness to lead the effort. This story was publicized widely in U.S. news outlets. Now in 2020 with lockdowns and social distancing, a new report called The Psychology of Loneliness: Why It Matters and What We Can Do (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2020) has been released by the current minister of loneliness, Barroness Diana Barran. It shares that people experiencing loneliness describe shame, fear, anxiety, and helplessness. These emotions can cause a person to withdraw further and become lonelier. There are risk factors due to social situations and personality types. Also, mental health problems such as depression or social anxiety can lead to loneliness. Clinicians worry that loneliness can cause cognitive decline and lead to dementia, or dementia can also result in feelings of loneliness. The Campaign to End Loneliness is trying to address the policies and social structures that will help to alleviate unnecessary suffering.

Back in the United States, in 2017, Holt-Lunstad’s continuing research on the influence of social relationships on risk for mortality, began to receive wider attention from the federal government, health plans, AARP, and other providers who were tracking mental/physical health and the actual dollars associated with loneliness and social isolation for a growing number of older adults. Health payers and providers tied positive social relationships with patient adherence to medications and treatments. Studies also continued to find direct ties between isolation and higher blood pressure, function of the immune system, and greater inflammation. Loneliness could induce a number of detrimental effects on physical as well as mental health, such as a high blood pressure, depression; or dementia (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010).

The prevalence of loneliness was captured in a 2018 survey by AARP that found that 35 percent of U.S. adults age 45 and older are lonely (47.8 million people). Rates of loneliness were 24 percent for people over 70, 36 percent for people age 60-69, and 37 percent for people ages 50-59. Shockingly, the rate of loneliness was 46 percent for people ages 45-49. Loneliness is a large and growing problem in the U.S.

Now with COVID and a global pandemic in 2020 and 2021, a report from the AARP Foundation and UnitedHealth Foundation found that the pandemic had led to two-thirds of U.S. adults (ages 18+) to say they are “experiencing social isolation and more than half (66%) agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused their anxiety level to increase, yet many are not turning to anyone for help.” (AARP Foundation, 2020). More than a third (37%) reported that COVID had made them feel depressed. A third of adults 50 or older said they did not look to anyone for support during the pandemic.

Loneliness is problematic for emotional health and it is, indeed, costly, especially with 51 million Americans over age 65 or older today. This population will reach 60 million by 2030. Medicare spends an estimated $1,643 more annually on “objectively isolated” beneficiaries than on individuals with great social connections (Shaw, et al., 2017). Estimates from health plans found between $1,800 to $3,800 more is spent per person annually on Medicare members who identified as lonely (higher hospitalization rates, more doctor visits, and higher pharma costs). If a beneficiary is widowed and isolated, Medicare estimates spend as $3,276 more per year than on people who are widowed (but not isolated) (Shaw, et al., 2017). Also, people who are more isolated used more skilled nursing services and had a 30 percent higher risk of death annually. Medicare reported that they spent $768 less per year on people who report that they are lonely, but this could be because lonely people have trouble accessing health care. Also, this study found that it is still the case that depression will predict higher Medicare costs. It came as no surprise to the researchers that older adults with poorer socioeconomic standing and poorer health overall were costing “the system” more each year. They recommended that clinicians ask questions about social isolation (Shaw, et al., 2017).

Studies from other countries are helpful in revealing some of the root causes of loneliness. In a U.K. study, widowhood, physical health problems, less intimate social relationships, and less or infrequent contact with family members were all reasons why loneliness happened. Keming Yang, at Durham University in the United Kingdom, studied data on risk factors for loneliness. Yang looked at data from more than 9,000 people age 50 and older to see changes that may have occurred over an 8 to 9-year period (using the UCLA Loneliness Scale). About 50 percent of participants in the study maintained the same scores over time. About 25 percent became more lonely; the remaining 25 percent became less lonely. About 2 percent reported severe loneliness that was consistent over time; identifying and building solutions for people in this group was the biggest need noted. It was interesting that not just the presence of their spouse or partner mattered, but the “perceived closeness to their spouse or partner” (Yang, 2018) had a significant effect on their level of loneliness. Still, the conclusion was that marital status, social relations, and health are predictors of loneliness or non-loneliness. People experiencing less loneliness were in a close relationship with their spouse (or partner), had more interaction with their children and close friends, and/or had a strong sense of good health (Yang, 2018).

In Canada, researchers looked at the person-environment (P-E) fit to see what factors explained loneliness. Data comprised a sample of 3,799 respondents over age 65 drawn from Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey, Cycle 22 (de Jong Gierveld, Keating, Fast, 2015). Personal characteristics such as widowhood, poor health (especially among women), economic insecurity, and poor social and family networks led to loneliness. They specifically noted that families need to have communication across the generations to maintain continuity and sense of belonging. Adult children are an important source of companionship, and close family does make a difference in lowering levels of loneliness. Also, friends and neighbors can step in and especially help those who never partnered or never had children. Church and community organizations were important as well for bringing people together and showing genuine concern for wellbeing and care. Also, general life satisfaction was also helpful in fighting loneliness (de Jong Gierveld, Keating, Fast, 2015).

In Sweden, one of the most heartbreaking but telling studies on loneliness came from qualitative interviews with 10 older adults who reported feeling lonely often or all the time. The interviews attempted to get to the heart of what life events or current life situations were causing these feelings. At the core, they had lost significant relationships and/or they were longing for more fulfilling ones, and this has led to emotional loneliness in old age (Tiilikainen & Seppanen, 2017). Disabilities and decreased social connection have been a part of the problem, and they longed for quality relationships (more than quantity). Some were widowed, divorced, or stayed single. Others had lost a close friend to death or they had trouble making friends always, or they had been separated from friends due to a move. Some reported trouble or a broken relationship with their own children. Others had endured the death of a child or never had children. Still others had traumatic experiences as a child, such as the loss of their mother or other painful memories, which had led to lasting despair. Sadly, due to the increase of their disabilities and the decrease of their social integration, the older people referred to loneliness as an inevitable part of aging. It is fearful to think that more people than we realize may have experienced some of these unknown traumas that are at the core of loneliness in the U.S. today; more research is needed.

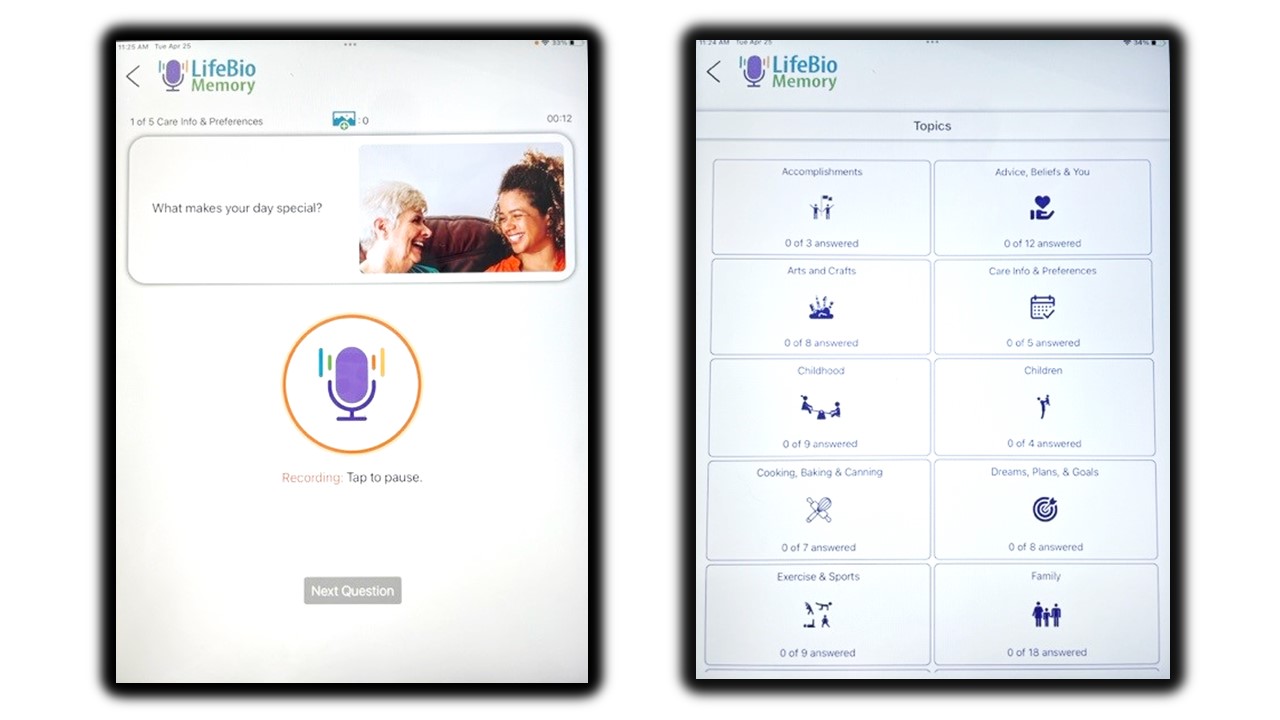

What can fight loneliness? Older adults who owned a pet were 36 percent less likely to report loneliness than older adults not reporting pet ownership (Stanley, et al., 2017). Exercise can also have a positive impact on reducing loneliness and increasing social connection, even when people are living with a physical impairment (Boekhout, et al., 2019). In the Netherlands, an intervention called Active Plus65 was tracked that improved social connection and stressed work arounds for how to still participate even with health or physical limitations. Participants were sent marketing materials and encouraged to participate online. At the 3-month and the 6-month mark, participants were more physically active. The exercise and the social aspects of the program both worked. Another positive example of building new social connection was in an affordable senior housing building where residents live independently. With a social room in the building and a fun calendar of weekly events and a healthy concept of “time left,” they developed good social supports upon moving in (Drum & Medvene, 2017). Most estimated that they and their fellow residents would be alive for at least five years. Ten percent of people made very close friends and 42 percent had at least acquaintances or casual friendships in the building. Social isolation was still a concern for about 44 percent of the residents, but that was lower than the 49 percent of assisted living residents (who typically maintain more external help from family) in a comparable study (Drum & Medvene, 2017). In 2018, a published study by Optum Insights and UnitedHealthcare found that LifeBio’s Capture Your Story program (offered a 6-week period by phone) was effective in engaging the 30 participants in a group intervention and capturing their life stories had reduced loneliness and improved social support (Keown, et al., 2018). It is important to note that this group continued beyond the 6-weeks and have been meeting weekly for over three years. Many of the participants in Capture Your Story are widowed, and they find great comfort and joy in their weekly visit with a group of phone friends to reminisce on a different topic each week.

As the field advances and is modified to scale to larger groups, current studies led by Optum, with contributions from UnitedHealthcare and AARP Services, Inc., are identifying the importance of Personal Determinants of Health (PDoH) (MacLeod et al. 2021). Things like personal resilience, purpose, optimism, and social engagement are being investigated to see how they impact physical and mental health. In the future, research on people 65+ in one-on-one loneliness intervention phone conversations, managed by LifeBio, Inc., with peers speaking with other peers will shed light on key outcomes. Measuring PDoH, loneliness, social support, and other factors are important in evaluating wellbeing of older adults served by health plans with more data to be released in the coming years. All signs point to real relationships forming by phone, even between two strangers who build a friendship, with the power of voice and listening.

Settings where people live, various social experiences, or mental health conditions can impact how loneliness is experienced and reported. In the case of home and community-based services, with elders living at home and receiving help with activities of daily living, different network types could be associated with loneliness, social isolation, and quality of relationships (Medvene, et al., 2015). The people experiencing the least amount of loneliness were receiving help at home from family or family/friends at the heart of their care. Participants in this study experienced more social isolation and loneliness if they had “restricted” networks which were considered paid caregivers delivering home care.

Widowhood, grief, and bereavement are all things to be addressed as they can lead to disconnection and loneliness. Damianakis and Marziali (2012) found that “creating meaning and purpose, a new or continued self, and social re-engagement” were all key to moving forward after the death of a spouse. Interviews in a bereavement group showed that participants were honoring their past relationship, while also entering new relationships, and socially re-engaging. They were changing, learning, and growing, and sharing their successes like inviting friends over for coffee. Gaining a new sense of self and renewed meaning and purpose mattered. Related to widowhood, another study used the Lubben Social Network Scale to survey 5,870 adults age 65 years and older, plus other measurements of loneliness and mental capacity were given (Peterson, et al., 2016). Widowhood was associated with 61 percent higher odds of reporting loneliness relative to being married. Men reported less loneliness compared to women. In addition, higher cognitive function was associated with lower reporting of loneliness. Significant chronic diseases were associated with 45 percent higher odds of loneliness (Peterson, et al., 2016).

Dementia is a topic of interest related to loneliness because it can impact feelings of social connectedness. In the case of Delores (my mother in law), as she was progressing with mild cognitive impairment and later early-stage dementia she would say, “I am so lonely.” It puzzled me as she would typically be surrounded by one or two family members when she would say this. It makes me wonder if changes in that area of her brain caused her to feel an uncomfortable and possibly terrifying feeling of disconnection.

Dementia has an impact on how people experience social structures and how they perceive relationships, thus loneliness can result. Some people cannot accept reality, or they may want to maintain very similar social relationships as in the past, but they are experiencing a new normal. Can the positivity remain when interacting with friends and family or will the person living with dementia withdraw, feeling they are inadequate? Burholt, Windle, and Morgan (2016) studied 3,593 people in Wales, measuring their social resources (LSNS), Townsend Disability Scale, loneliness (De Jong Gierveld Scale), and the MMSE for cognition. They found that disability and cognitive changes did have a significant effect on loneliness and new models are needed to maintain or improve social relationships (Burholt, Windle, Morgan, 2016). Can we truly become dementia-friendly people and communities? Another example in the U.S. found that poor social environments were associated with a greater risk of cognitive difficulty in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS) of 779 U.S. adults ages 70. One of their conclusions was that policies and services should be developed to promote a rich social environment in caring for someone with dementia. This is a growing need in the U.S. right now that will require new thinking and better family caregivers support too.

The negative aspects of group care homes (nursing homes) came from interviews on existential loneliness (EL) and its impact on 23 people ages 76-101 living in residential care facilities or in palliative care units in Sweden. People shared the feeling that they were trapped in a frail and deteriorating body. Also, they were being met with indifference, they had no one to share their lives with, they lacked purpose and meaning, and, at the core, they were being disconnected from life which led to great distress and suffering. With physical limits and illness and especially in care settings, people are lacking links to the regular world. A sense of worthlessness sets in and meaninglessness follows, leading to disconnection and despair.

Significant themes in the individual interviews were noted with the most often themes mentioned first. The list is painful to read with the mental suffering that must be associated.

- I feel trapped by physical limitations

- I am lacking a meaningful everyday life

- I feel left out of community

- I miss someone to share my thoughts and interests with

- I feel betrayed by people of importance

- I feel left behind

- I feel that no one sees me as a unique person

- I don’t feel at home

- I feel exposed to others

- I long for spiritual contact

- I long for intimacy

- I am tired of waiting for someone to come

- I fear what will come

- I feel useless/helpless

- I feel that no one is interested in my cherished possessions

- I feel emptiness and loss

- I am done with life

- I am ashamed of and feel guilty about the person I have become

Each one of these statements could be analyzed and solutions could be identified if possible. Clearly, loneliness is a negative experience as an individual knows that something is truly missing from life. It is can be a feeling of estrangement and possibly physical isolation too. One of the saddest stories from LifeBio’s program called MyHello was an 85-year-old woman who was isolated at home due to health problems and no transportation. She sadly shared, “If I don’t see my mail lady, I don’t see or talk to anyone all day.” Another woman in her mid-70s said, “Can we move my MyHello phone call to Saturdays? There is no chance that anyone will call me (like my friend or even my doctor) on Saturdays so that is the hardest day of the week.” We moved her weekly call to Saturdays as a result. Sometimes it is that family has moved away and physical problems (such as having to use an oxygen tank) or no longer driving makes getting out very difficult. Sometimes the person’s self-image is knocked down and they feel they are not worthy of human companionship, or they may believe that close family or friends are withholding their love, care, and presence. Strikingly, it is even possible to be in the same room with friends or family and still feel detached and lonely.

In contrast to loneliness, solitude is being alone without being lonely. It is a positive experience as one is engaged with the self and not minding the aloneness. It feels sufficient, and it can be a time for reflection, growth, joy, and peace. Sometimes solitude leads to reading, truly experiencing the beauty of the natural world, or a time of rest, relaxation, and recharging. Solitude can be a time for spiritual growth, prayer, deep thoughts, creativity, painting, crafting, writing, or other endeavors. (Estroff Marano. 2003). Solitude needs more attention as a positive pursuit, especially in the time of COVID-19.

Solitude brings the mind and soul back into alignment. In the literature, there were positive examples of elders who were enjoying solitude in their old age and not experiencing loneliness. This gives us hope that loneliness is not necessarily a plague of old age. A researcher at Assumption College in Worchester, Massachusetts, interviewed 39 women that were “Elder Women Religious” (Catholic nuns). In the case of 77 percent of the women, the activity theory, disengagement theory, and gerotranscendence theories of aging were all present in their lives, resulting from data gathered in the life review interviews (Melia, 2001). In the remaining 23 percent, they maintained high levels of activity in their lives as they were still working in their old age. Some enjoyed part-time work, others volunteered, attended meetings, did housework, or made crafts to support mission efforts.

When the women were asked “what gives them happiness and pleasure in late life” (Melia, 2001), they focused on their strong relationships with their religious sisters, friends, family, nature, music and art, hobbies (including travels and shopping), helping others, and sharing events and activities with others. They enjoyed giving back and serving others, and they served God by having something to offer. Although activity levels had slowed, and disengagement theory occurred, social activities continued as part of gerotranscendence. Of the 30 that had withdrawn from social roles and regular interactions, 87 percent said that this happened for positive pursuits of having more “quiet time, slowing down, speaking with God, praying, meditating, having time for one’s self and time for God, time “to be,” reading, dreaming, reflecting, and, in some cases, preparing for death. It was valuable time for women who ‘like to be alone.’ There was more time for God, to slow down and ‘rest with the Lord.’ Another respondent shared, “My pleasure right now is to go to chapel and pray and be quiet. But now I have the time. I’m free. So, whenever I feel like it, I go to the chapel. There’s no set time, no set length. And I can do the amount of praying that I want and no praying if I don’t want. And I just sit there and tell the Lord I love Him and here I am.” (Melia, 2001).

In this case, solitude is a spiritual activity that is valuable; they do not feel isolated or withdrawn. They feel close to God and they embrace the solitude for these times to pray and think. Another respondent said, “I am a very happy old lady.” (Melia, 2001). Prayer and spiritual pursuits lead to releasing worries and embracing trust and acceptance. People determining solutions for loneliness should closely examine the benefits of spirituality and faith in the lives of older adults and how to ignite these feelings as a means of protection in old age. One more quote was telling. “We have learned to know God more and as you know Him you grow deeper and deeper into the arms of God and love Him more because He first loved you.” The feeling of external love from a spiritual source can be helpful in reducing a sense of isolation; this woman does not feel that she is ever alone.

One last example of positive life experiences in old age comes from 17 centenarians in Poland. Qualitative research was conducted to find factors that protected them against loneliness. They found a high level of optimism in the centenarians. Also, they were staying active as much as possible and physically or mentally working. They had positive social relationships as well. All these factors contributed to protection against loneliness (Mackowicz & Wnek-Gozdek, 2018). Despite socioeconomic diversity, their participation in lifelong activity (activity theory), both physical and intellectual, and an optimistic outlook to life, were the secrets to successful aging. Perhaps their physical health had also helped result in emotional well-being and resilience. They went to meetings, participated in conversations, took walks, watched TV, prayed, painted, and organized events. This study is important as it can be used to prevent loneliness if people are aware of what can help personally or even as a family support system. Positive social relationships serve as protection against loneliness among the oldest old. An optimistic attitude and persistence in activity may have contributed to good relationships among their closest social connections. Also, the need for purpose and meaning (such as meaningful work and not just leisure) is something that should not be discounted as people reach old age.

This topic is a reminder of the magnitude of the problem at hand and how critical it is to address the “elephant in the room” (loneliness/isolation) when speaking with older adults or designing programs in the future. Acknowledging the problem and sharing proactive solutions may help older adults see the issue and protect themselves from adverse mental and physical conditions. At LifeBio and MyHello, we will continue to stress the importance of LIFE STORY WORK and REMINISCENCE as a tool for social connectedness as it gives purpose and meaning, it shows how resilient people can be over time, it helps create a lasting legacy which can engage generations, and it is something that brings feelings of integrity and self-worth. The stories we hear from participants in MyHello help us continue to see the value in bringing people together to build friendships and to listen to each other’s stories. New questions and challenges have emerged as well, and these will not be easy solutions. For example, as we are developing online tools for engagement with people living with Alzheimer’s and their care partners (LifeBio Memory is in development), can technology reinforce social connectedness and give a sense of belonging in its interface? When we continue to develop software for MyHello and measure outcomes, how can we support efforts to reduce loneliness and build friendships and connection through the user experience on tablets or phones? As we work with nursing homes across the U.S., should information on the feelings people have as they are isolated in their rooms be shared with the staff so they see the engagement using LifeBio and reminiscence as both urgent and important to overall wellbeing? What additional training do my staff members or present/future clients need to better address loneliness and isolation while also encouraging solitude as a positive experience? As a true solution that already exists for loneliness, the most important thing is to expand the clients we serve so millions can have access online, by phone, or face to face to the social connectedness that comes through narrative care and storytelling.

In summary, loneliness and social isolation are growing problems in the U.S. and worldwide and researchers have identified health and disabilities, lack of meaningful social connections (do family and friends truly connect?), and physical isolation are just some of the core issues facing older adults. Identifying if people have Personal Determinants of Health, such as resilience, will be of growing importance. In addition, specialized approaches are needed to help people experiencing loneliness when they have dementia, and new strategies for social connectedness are needed to address widowhood and grief. Extra attention and new approaches should be implemented in residential care (senior living), nursing homes, and hospice/palliative care units (in hospitals) because of the unique challenges that some people face when they are frail, hopeless, and in a constant lonely state of mind. On the positive side, efforts should be focused on increasing opportunities for practicing spirituality and faith as a “fighter” against loneliness, and lessons from centenarians clearly show that purpose, meaning, work, resilience, and social connectedness are all personal determinants of health that can be encouraged in old age to stave off loneliness, isolation, helplessness, depression, and meaninglessness. Big challenges are ahead and many will need to be part of solution.

References:

AARP Foundation (2018). Loneliness and Social Connections: A National Survey of Adults 45 and Older (aarp.org). doi.org/10.26419/res.00246.001

AARP Foundation & UnitedHealth Foundation (2020). The Pandemic Effect: A Social Isolation Report https://connect2affect.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/The-Pandemic-Effect-A-Social-Isolation-Report-AARP-Foundation.pdf

Boekhout, J.M., Berendsen, B., Peels, D., Bolman, C. & Lechner, L. (2019) Physical Impairments Disrupt the Association Between Physical Activity and Loneliness: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 2019(27), 787-796. doi:10.1123/japa.2018-0325

Burholt, V., Windle, G., & Morgan, D.J. (2016). A social model of loneliness: the roles of disability, social resources, and cognitive impairment. Gerontologist, 2017, 57 (6), 1020–1030. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw125

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived Social Isolation Makes Me Sad: 5-Year Cross-Lagged Analyses of Loneliness and Depressive Symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463.

Campaign to End Loneliness (2020). The Psychology of Loneliness: Why It Matters and What We Can Do. https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Psychology_of_Loneliness_FINAL_REPORT.pdf

Damianakis, T., & Marziali, E. (2012). Older adults’ response to the loss of a spouse: The function of spirituality in understanding the grieving process. Aging and Mental Health, 16(1), 57–66.

de Jong Gierveld, J., Keating, N., & Fast, J. E. (2015). Determinants of Loneliness among Older Adults in Canada. Canadian Journal on Aging, 34(2), 125–136.

Drum, J. L., & Medvene, L. J. (2017). The social convoys of affordable senior housing residents: Fellow residents and “Time Left”. Educational Gerontology, 43(11), 540-551. doi:10.1080/03601277.2017.1344081

Estroff Marano, H. (2003b, July 1). What Is Solitude? Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/articles/200307/what-is-solitude

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T.B., & Layton, J.B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). The Potential Public Health Relevance of Social Isolation and Loneliness: Prevalence, Epidemiology, and Risk Factors. Public Policy & Aging Report, 27(4), 127-130. doi:10.1093/ppar/prx030

Keown, K., Tkatch, R., Martin, D., Duffy, M., Wu, L., Schaeffer, J., Wicker, E. (2018) LifeBio: Life stories of older adults to reduce loneliness and improve social connectedness. Innovation in Aging, 2(1), 241, https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy023.899

MacLeod, S., Kraemer, S., Tkatch, R., Fellows, A., Albright, L., McGinn, M., Schaeffer, J., Yeh, C. (2021). Defining the Personal Determinants of Health for Older Adults. Journal of Behavioral Health, 10(1), 1-6.

Mackowicz, J. & Wnek-Gozdek, J. (2018) Centenarians’ experience of (non-)loneliness—life lessons. Educational Gerontology, 44 (5–6), 308–315. doi:10.1080/03601277.2018.1473969

Medvene, L. J., Nilsen, K. M., Smith, R., Ofei-Dodoo, S., Dilollo, A., Webster, N., Graham, A., Nance, A. (2015). Social networks and links to isolation and loneliness among elderly HCBS clients. Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 485-493. doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1021751

Melia, S. P. (2001). Solitude and prayer in the late lives of elder Catholic women religious: activity, withdrawal, or transcendence? Journal of Religious Gerontology, 13(1), 47–63.

Ong, A., Uchino, B., Wethington, E. (2016) Loneliness and Health in Older Adults: A Mini-Review and Synthesis. Gerontology (62) 443–449, doi: 10.1159/000441651

Peterson, J., Kaye, J., Jacobs, P., Quinones, A., Dodge, H. Arnold, A. Thielke, S. (2016) Longitudinal relationship between loneliness and social isolation in older adults: results from the cardiovascular health study. Journal of Aging and Health, 28(5) 775–795. doi: 10.1177/0898264315611664

Poey, J. L., Burr, J. A., & Roberts, J. S. (2017). Social Connectedness, Perceived Isolation, and Dementia: Does the Social Environment Moderate the Relationship Between Genetic Risk and Cognitive Well-Being? Gerontologist, 57(6), 1031–1040.

Shaw, J., Farid, M., Noel-Miller, C., Joseph, N., Houser, A., Asch, S., Bhattacharya, J. & Flowers, L. Jonathan G. Shaw. (2017). Social isolation and Medicare spending: among older adults, objective isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. Journal of Aging and Health, 29(7), 1119-1143. doi:10.1177/0898264317703559

Stanley, I. H., Conwell, Y., Bowen, C., & Van Orden, K. A. (2014). Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging and Mental Health, 18(3), 394–399.

Sjoberg, M., Beck, I., Rasmussen, B., Edberg, A. (2017) Being disconnected from life: meanings of existential loneliness as narrated by frail older people. Aging & Mental Health, 22(10) 1357-1364. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1348481

Tiilikainen, E. & Seppanen, M. (2017) Lost and unfulfilled relationships behind emotional loneliness in old age. Ageing and Society, 37(5) 1068-1088. doi: 10:1017/S0144686X16000040

Yang, K. (2018). Longitudinal Loneliness and Its Risk Factors among Older People in England. Canadian Journal on Aging, 37(1), 12–21.